I work with distributed systems on a daily basis, and having come across the book “Designing Distributed Systems by Brendan Burns (O’Reilly). Copyright 2018 Brendan Burns, 978-1-491-98364-5.” I was interested in knowing if some difficulties that I’ve faced have been crystallized in the form of microservices design patterns, and more importantly I’m looking to learn new interesting ways to solve upcoming challenges.

The book is freely available on the Microsoft Azure resources website

Although I’m still going through the first chapters, the book comes across as directed towards docker containers orchestrated by kubernetes. It starts by presenting a single node pattern, the sidecar.

So, why do I need a sidecar?

You want to add a responsibility to your container that doesn’t really fit with its core purpose, you want the ability to dynamically add or remove such responsibility. The sidecar microservices pattern resembles the decorator pattern: your client will always be interested in the core functionality of your container, and not necessarily about the functionality provided by the sidecar.

The book shows a couple of examples where a sidecar can be used to improve a legacy application (a legacy app that can live in a container, definitely not your run-of-the-mill legacy application ^̮^ ), by making the sidecar act as a https reverse proxy to a legacy application or a WebApi configuration interface to an application that without the sidecar could only read the configuration from files.

Nevertheless, the sidecar container could also be used on modern containers to provide application health telemetry. I imagine a container that plugs into the JMX interface (Java Management Extensions) of any Java virtual machine and provides a common REST API for any such container. Introspection on container’s resource usage could also be an interesting use case to detect faulty or malicious behaviour.

Right, and how is it done?

A sidecar container should act in symbiosis with the core functionality container. With docker, we have a few ways to do this:

Interception

This happens when you intercept the traffic that would otherwise reach your container directly. In this usecase you’d have a reverse proxy running in the container where you’ll setup what will be forwarded to the original container (everything, if your sidecar just adds https; or perhaps just urls matching a wildcard, if your sidecar is adding endpoints for application health monitorization).

In this scenario you will create a virtual network between the two containers ensuring that nobody other than the sidecar can reach the core functionality container. Furthermore, you’d make sure that the sidecar is the one exposed to external traffic.

Shared resources

In this case the sidecar runs along with the core functionality container but has access to the same resources. For instance, this can happen because both containers share the filesystem (see example on how to setup loggly), or the PID space (this nice article from Vish Abrams details the approach and it’s shortcomings).

What will we build to consolidate this knowledge?

Getting your hands dirty is a good way to consolidate knowledge: If I wanted to experiment with the sidecar pattern then the first thing to do is to decide on a core application and it’s sidecar.

The core functionality

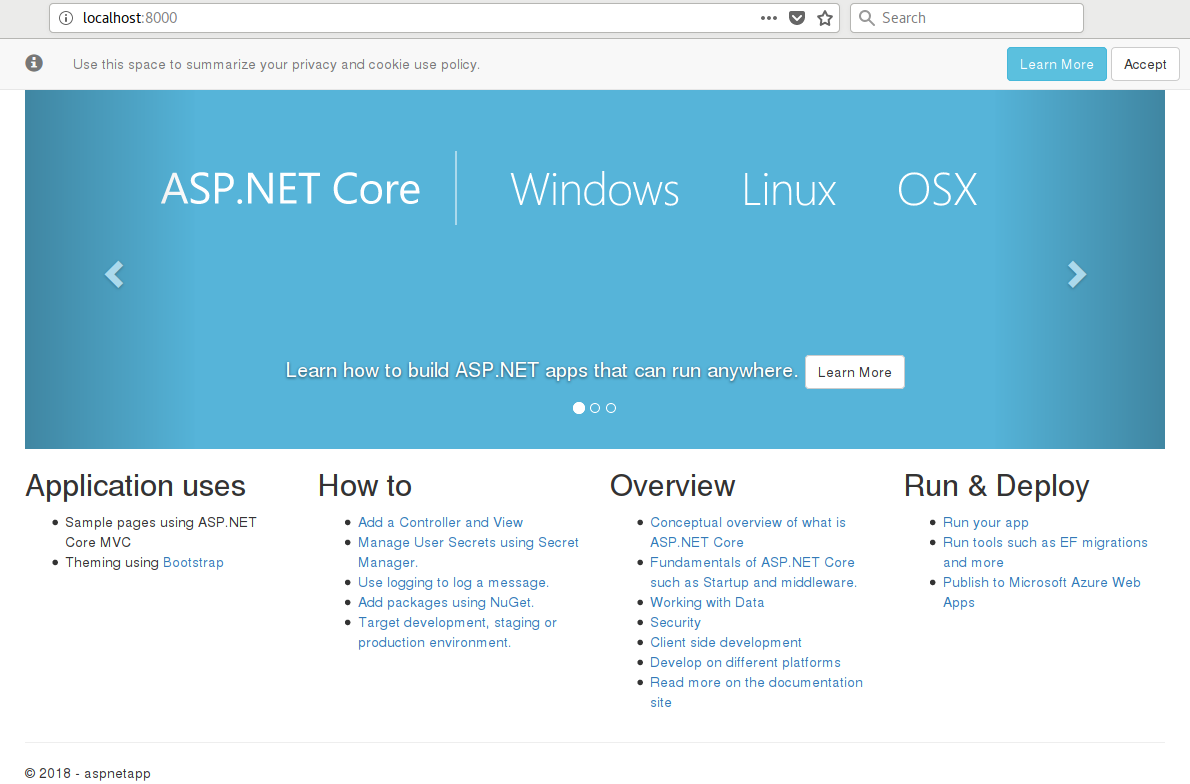

I’ll use the Microsoft example ASP.net container as an example, as provided in the dotnet-samples registry.

The container is started with a simple command:

docker run -it --rm -p 8000:80 --name aspnetcore_sample microsoft/dotnet-samples:aspnetapp

And sure enough, after a while the application is available in localhost, port 8000:

The sidecar

Instead of choosing an existing sidecar I decided to create one myself. These containers are running Linux and I thought that having a WebAPI for the strace utility would be nice and reusable. strace is a diagnostic and debugging utility, able to display the system calls that a given process is doing. With this API we can get a glimpse into the IO operations that an app is doing (network connections, open files).

Feel free to take a look at the sidecar container, I’ve made it publibly available in github, at https://github.com/brunoflavio-com/strace-api.

Building the strace-api

This is for learning purposes, so lets keep it simple: The goal was to plug the strace output into a WebAPI controller. With the help of micronaut this was really simple to get done.

Starting from the Creating your first Micronaut app guide I quickly got to the desired result:

Building the sidecar container

The micronaut guide already included a Dockerfile, that’s nice! It’s based on the alpine linux distro and the only change I needed was to install the strace package while building the container:

FROM java:openjdk-8u111-alpine

RUN apk --no-cache add curl

RUN apk --no-cache add strace

COPY build/libs/*-all.jar strace-api.jar

CMD java ${JAVA_OPTS} -jar strace-api.jar

As stated in the book, in order to be really useful we need to treat the container as an API and try not to break it. I should have exposed more variables to the container user in order to specify at least the PORT.

Building and running the strace-api is achieved as follows:

./gradlew assembleShadowDist

docker build --tag=strace-api .

docker run -p 8080:8080 --cap-add sys_ptrace --cap-add sys_admin strace-api

Getting things to work together

Now that we have a core container and we’ve built our own sidecar, let’s try to make them work together! In this case we want to share the PID space, i.e. the sidecar should be able to reach the processes running in our core container in order to be useful.

Starting the core container

We start the code container first, as usual:

$> sudo docker run -d --rm -p 8000:80 --name aspnetcore_sample microsoft/dotnet-samples:aspnetapp

efce386c695ce8f0d1ebf09f2c423a696670eaa84491f300528b37be546e1318

The hex number returned is the container id, we’ll need it to connect to the sidecar.

Starting the sidecar

The sidecar needs to be started in the same PID space, this is done with the --pid=container:container-id parameter:

$>docker run -d --pid=container:efce386c695ce8f0d1ebf09f2c423a696670eaa84491f300528b37be546e1318 \

-p 8080:8080 --cap-add sys_ptrace --cap-add sys_admin strace-api --name strace-api

fd501b5f1877c84e4b412528d6a06fb83fc65c5c8da3d8fb6b87ab2981058912

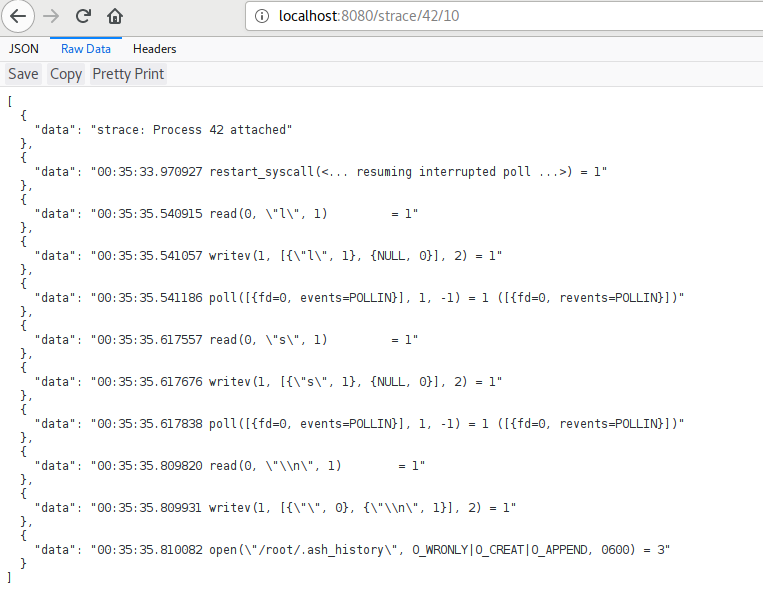

Inspecting the core container system calls!

In order to use the strace-api you need to pass the intended process id, it should probably include a resource to list running processes. In this case I used the sidecar container to find out the PID our dotnet application was running on:

$> docker exec -it strace-api sh

/ # ps -A

PID USER TIME COMMAND

1 root 0:01 dotnet aspnetapp.dll

55 root 0:00 /bin/sh -c java ${JAVA_OPTS} -jar strace-api.jar

62 root 0:06 java -jar strace-api.jar

255 root 0:00 sh

264 root 0:00 ps -A

/ # exit

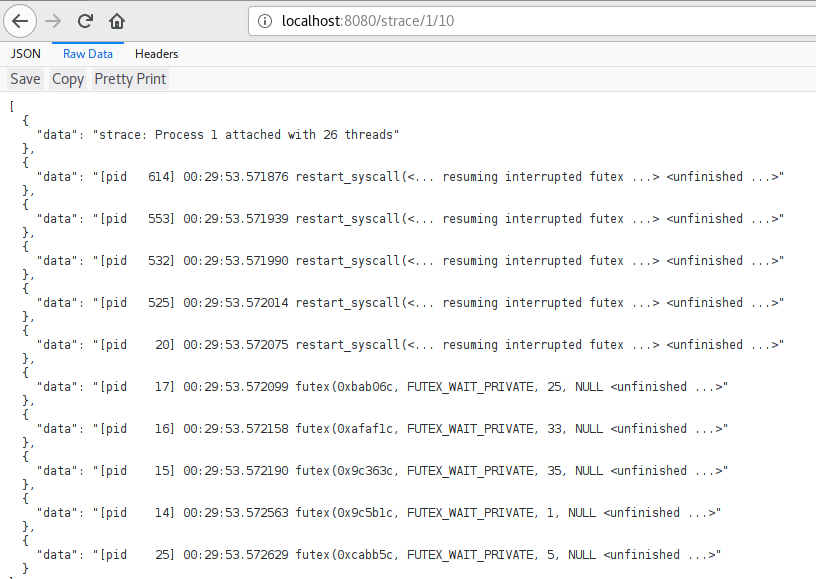

There we have it, the PID we’re looking for is 1. Let’s head to http://localhost:8080/strace/1/10 to see what it is doing:

In case you’re wondering what the 10 stands for in the url, it’s the number of strace lines that we want to read. Well, here it is, an application that provides a core functionality - an asp.net core website - that was improved with a sidecar that allows for kernel call inspection.

Conclusion

Just like the decorator design pattern, the sidecar allows us to dynamically add functionality to a core container. This is only possible due to the extensive capabilities that docker and the other Linux kernel components provide, allowing containers to communicate via virtual private networks, share the PID space or even the filesystem.

Sidecars are a useful addition to the devops toolkit and Site Reliability Engineers will certainly see the benefit of building standard sidecar containers that then will provide uniform information (logging, introspection, resource monitoring, failure and malicious activity detection, etc…)